Thanks to Airk for his question in comments to the creating characters article. His question was about brainstorming scenes, particularly how I brainstormed and tricks for inspiration.

Mostly how you structured your brainstorming and any tricks you might have for inspiration; When I’m designing scenes, I have a tendency to get sort of bogged down writing down too much stuff, or throw my hands up in the air and say “Well, if the players haven’t derailed the game by this point I guess I’ll just have to wing it.”

Sounds like a good outline to me!

Scene Brainstorming Structure

I began with the understanding that this was a demo game of a system. One goal for the scenes was to introduce the rules interestingly–not so slow that it’s the videogame tutorial where your troops whack scarecrows, but not so complex that everyone feels lost from the beginning and disengages.

The second element guiding my scenes was the knowledge that the characters would be new to the players too, given its design as a one shot. I like to work in a character development scene relatively early, so that I can see how this version of Ivan Notovisk is in play. Even in a campaign where I get to plan out a character, I often learn that they’re different in actual play as soon as they interact with other PCs. Many other players make the same adjustments.

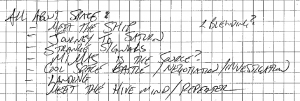

The third element–and really, the one that fires the imagination–came from filling in the bones of Troy’s plot. The world is responding to the alien messages, but how? They’re sending Earth’s best out to study the anomaly. They have a ship, and it’s constrained by near real world physics. So, let’s begin by introducing the characters to each other… and their home for the next sixteen plus months, the ship.

The first scene set the mission in motion. The characters got to interact, some characters meeting their peers for the first time. That allowed me to see which traits the players latched onto, and which they downplayed. There weren’t any mechanics in this scene; I could have introduced a minor challenge to demonstrate the system, but decided to handle that in the second scene.

Scene two was a chance to demonstrate growth and development; a way to see how the players imagined their characters having adjusted to a life in space. Were they still excited after two months of drudgery? Did any of the characters come to regret getting crammed into a tin can with little personal space? I introduced the mechanics, asking what projects (if any) they’d pursued over the months so far. Their answers really developed their characters, revealing their passions to their fellows.

But I didn’t end the scene there. I knew that even though the game was going to be a lot less butt-kicking than Fate Accelerated’s norm, I didn’t want it to be dull either! So after we saw how the characters had handled the first months of space, a micro-meteor went “ping” and their air pressure readouts started to sink.

This allowed characters to show a different, spontaneous, side to their characters. The mechanics weren’t very complex–a challenge, rather than a context or conflict–but the dice conspired to keep it complicated. A brief epilogue to the scene allowed other characters to show off their own contributions. I hadn’t planned on the “repair and recovery” transition, but it let everyone shine, and continued to demonstrate their competence.

Scene Recording

Once I have a good idea for a scene, I try to record it briefly. You mentioned in your question getting wrapped up and writing too much. I have written too much many times before–for my Mage game in Cleveland, I often spent several paragraphs on a location. Writing too briefly can also be a flaw: how many of us have wandered through dozens of rooms and only noted the monsters we encountered?

A template might work well for you–-Matthew’s Quick and Dirty Location Template is great place to start. It has plenty of detail for multiple linked locations, or for a place where the PCs can let their eyes linger. My own descriptions tend to be more abbreviated: a few descriptive notes and two or three situation aspects (in Fate, specifically, but the technique carries over to other systems). Part of the reason I use situation aspects is to remind myself that active terrain and opportunities are what make scenes sing. The best part of a crowded bar isn’t the description of stale beer, but knowing that if you dive under a table, there are lots of knees to bump into. Or if you don’t have weapons, you can pluck darts from the board and keep your opposition distracted.

Combine an interactive location with opposition or a threat–-even a natural threat–and you’re set. Evocative Scenes on the Fly has a few variations, but I continue to enjoy writing scenes on 3×5 cards.

Summary: A title line for “what the scene’s about”–“May 24th”, “Attack at Ceres”, or “Peaceful Glade”. A line or two listing who’s present and their goals. (Vampire Count: Humiliate rival by revealing lair.) Two or three lines (or aspects) to set the scene–description, hopefully useful to inspire players and encourage interaction with the terrain. Use multiple senses to establish an element if possible. That’s most of a 3×5 card. Of course, you still have the back to remind you of “mid scene” developments, reinforcements scheduled to arrive, or tactics if an NPC can do something unusual. Or if there’s something you don’t want to forget–like, “must drop incriminating note as she flees”.

Techniques from the Crowd

Do you have a sure-fire way to record the right information to bring scenes to life at the table? Please share your techniques! Or, if you have a trick for brainstorming a scene worth recording in the first place, that’s always handy.

It’s intriguing to see how other people approach the same situations. Until you posted this series of articles, I hadn’t really considered how I prep for sessions. Now I’ve formalized my methods and even posted my approach. http://violentmediarpg.blogspot.com/2013/07/definitely-maybe-it-depends-and-free.html

Thank you, sir.

Once more Gnome Stew chums the waters of my mind bringing to the surface idea-sharks great and small (and weird metaphors).

I liked your article–good stuff!

Thanks for this; I’ve given it a quick skim for now and it seems very helpful, and I’ll be going back over for a serious readthrough when there’s more time.

I’ll also check out randite’s article, thanks!

So, gave this a more thorough onceover, and I’m really liking the (perhaps obvious) idea of having a clearly defined purpose (narratively speaking) for each scene.

Randite’s writeup is good too, but for a different type of game – the last game I ran was Tenra Bansho Zero, which is a highly cinematic, scene-and-narrative driven game, which is what had me struggling a bit for scene ideas. Randite’s format is good one for more traditional non-scene-based campaigns/adventures (One of which I’ll be running soon, I think), though those are usually easier for me to frame.